Testo di Francesco Di Traglia

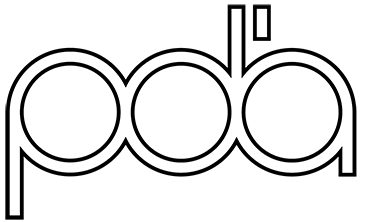

1 – Corteo di Teodora

A un occhio raffinato un’opera d’arte appare come una immensa biblioteca in cui sono racchiuse storie di popoli, aneddoti, visioni del mondo, rimandi culturali. In questo sottile gioco di specchi e nella facoltà di tessere la trama di un’opera sta il valore di essa e la grandezza di un artista. In più, ogni qual volta ci si fermi a riflettere sul passato e sulla necessità di rileggerlo o di confutarlo un sistema va in crisi e ci si ritrova a un gradino più in alto nella ricerca.

Ogni artista, che lo voglia o no, ha a che fare con la tradizione; e già il fatto di rifiutarla o di demistificarla è di per sé una nuova affermazione di essa.

Le Avanguardie storiche e le Neoavanguardie hanno riflettuto spesso sul rapporto con la tradizione e alla luce di tali esperienze oggi ci chiediamo se ha ancora senso porsi il problema di considerare il passato. Sembra quasi, infatti, che lo spirito della ricerca contemporanea abbia come primo obiettivo quello di lasciare un’impronta indelebile, talvolta utilizzando linguaggi provocatori, violenti o irriverenti, nel tentativo di liberare l’arte da questo labirintico gioco di rimandi e affermare definitivamente lo spirito del tempo presente.

2 – G. Klimt, Giuditta

Eppure, a ben vedere, anche questo tentativo ha in sé il germe del fallimento dato che nel passato furono in molti a percorrere questa strada, certo con linguaggi diversi, ma con i medesimi intenti. Ancora una citazione, quindi, di nuovo un ricadere nel già sperimentato. Resta infine da considerare il fattore tempo che nel giro di qualche decennio trasforma in tradizione ciò che all’epoca della sua nascita si presentò come avanguardia.

Appare chiaro che dalla tradizione non ci si può liberare giacché essa rappresenta il vocabolario di forme e metodologie senza le quali il discorso artistico perderebbe i propri strumenti di lavoro. Sarebbe come tentare di scrivere un testo rifiutandosi di utilizzare delle parole. Allora, se dalla tradizione non si può prescindere, si può almeno tentare di sfruttarla per creare nuovi linguaggi e allargare gli orizzonti? Riteniamo di sì e alcune considerazioni di carattere storico possono aiutarci.

L’idea dell’originalità esclusiva è di matrice romantica; è nella prima metà dell’Ottocento, infatti, che emerge il culto della personalità singola, il suo valore di rivelatore privilegiato e solitario di forme e mondi, l’affermazione di una volontà titanica di opporsi all’omologazione sociale. Da qui la sensibilità dell’artista maledetto, il suo anticonformismo, il suo genio solitario. Prima di tale periodo la percezione della genialità dell’artista era diversa.

Nel Cinquecento il temine comincia a circolare nei trattati sull’arte legando il concetto di genio (etimologicamente forza produttrice) a quello di ingegno, quindi capacità di plasmare la materia per avvicinarla il più possibile all’idea. In questo contesto, però, sia colui che realizzava un’opera, sia colui che era in grado di copiarla o di citarla appartenevano alla stessa categoria perché entrambi capaci di utilizzare stessi metodi e strumenti. Su questo principio si basa ad esempio il Manierismo che attinge continuamente al vocabolario michelangiolesco per creare opere di ingegno; saper lavorare alla maniera di Michelangelo significava partecipare al suo genio e in questo atteggiamento non c’è rottura con la tradizione, ma continuazione di essa.

Un altro aspetto da considerare e che si rivela come vero catalizzatore dell’innovazione artistica è il concetto di empatia con l’opera d’arte. Con questo termine si indica la capacità di immedesimarsi nell’altro e conseguentemente anche con il frutto della sua sensibilità, il prodotto artistico. Questa caratteristica conduce a un’intima negoziazione dei significati tra produttore e fruitore e si avvale anche del substrato culturale di chi osserva. Ciò comporta che in base alla quantità e alla qualità della cultura di ciascuno, in definitiva a una sorta di tradizione personale, la lettura di un’opera e la sua eventuale citazione in un nuovo prodotto artistico sarà differente da soggetto a soggetto.

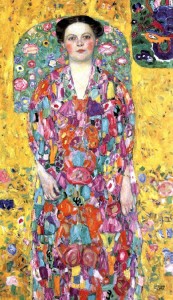

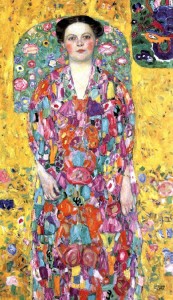

3 – G. Klimt, Ritratto di Eugenia Primavesi

Per esemplificare il discorso possiamo far riferimento ad artisti di epoca differente che hanno interpretato in maniera del tutto personale alcuni concetti tradizionali. Il primo è il pittore austriaco Gustav Klimt (1862 – 1918). Egli ha riflettuto in tutto il suo percorso artistico sul ruolo della decorazione realizzando opere affascinanti e ricche di rimandi alla tradizione. Tra i periodi della storia prediletti dell’artista c’è il mondo bizantino, con il suo sfolgorio di oro e materiali preziosi, il gusto per la copertura totale delle superfici e la spiccata bidimensionalità delle immagini. Egli ha saputo rileggere una tradizione secolare alla luce delle tendenze artistiche di fine Ottocento individuando in un’arte essenzialmente religiosa elementi formali da riutilizzare. L’operazione di Klimt non fa altro che depurare i caratteri prevalenti dell’arte orientale e ravennate [fig. 1] dal substrato culturale che l’ha prodotta, incastonando temi e tecniche in un nuovo contesto; della tradizione rimane la raffinatezza e l’allusione, mentre la sacralità lascia il posto a una materia spiritualizzata di una visione laica e decadente [fig. 2]. Gli stilemi bizantini del periodo d’oro permangono trasfigurati anche nel cosiddetto stile fiorito in cui la preziosità di materiali lascia il posto al virtuosismo della pittura, anch’essa deliziosamente cesellata [fig. 3]; ed è qui che l’innovazione appare compiuta, poiché la tradizione è stata pienamente assorbita dall’artista e non ha più motivo di essere palesata in quanto perfettamente compresa. Esiste ancora un sentore bizantino in questa pittura, che è antica e moderna insieme, perfettamente inserita nella tradizione eppure indubbiamente innovativa.

ORIGINAL QUOTES

Text by Francesco Di Traglia, translations by Laura Dumbrava and Luigi Cavallo

1 – Corteo di Teodora

For a talented eye a piece of art appears as a huge library in which people’s histories, anecdotes, world visions, cultural references are enclosed. In this slight game of mirrors and in the capacity of weaving the plot of a work can be found their value and the greatness of an artist. Furthermore, sometimes a person stops and meditates on the past time and on the necessity to read it once more or to refute it, a system goes into crisis and you are in a higher step in the research.

Each artist, whether he likes it or not, deals with tradition; the fact of refusing it or demystify it means maintaining it.

Historical avant-gardes and new avant-gardes often reflected upon the relationship with tradition. Thanks to those reflections nowadays we wonder if the problem of considering the past still makes sense. It seems, indeed, that the spirit of contemporary research has as first target to let an indelible mark, sometimes using challenging, violent or insolent languages in order to release art affirming definitively the spirit of present time.

2 – G. Klimt, Giuditta

However, if you think about it, even this attempt has in itself a failure since this way was used a lot in the past, of course with different languages, but with the same purpose. One more quote, then, backing doing what has already been tried again. In the end we have to consider the time factor which in some years converts into tradition everything used to be avant-garde.

It is clear that we cannot release ourselves from tradition as itself represents the vocabulary of shapes and methodologies without which the artistic discourse would lose its own work instruments. It would be like trying to write a text by refusing to use the words. But then, if we cannot give up tradition, could it be possible at least to try to exploit it in order to create new languages? We consider it as a yes and some considerations of historical nature can help us.

The idea of exclusive originality is Romantic; it’s in the first half of 19th century, indeed, when the cult of individual personality makes its appearance as well as its value of privileged and lonely revealer of shapes and worlds, a titanic will asserts itself opposing the social standardization. From all of this the sensibility of the cursed artist, his nonconformism, his lonely genius. Before that period the perception of artist’s genius was different.

In the 16th century, the term started to be used in art treaties, connecting the concept of ‘genius’ (‘productive force’) with the one of ‘intelligence’, in other words, the genius has the ability to shape the matter in order to bring it as near as possible to an idea.

But in this context both the one who created an artwork and the one who was able to copy it or quote it belonged to the same category because both of them were capable to use the same methods and instruments. On this principle it is based, for instance, the Mannerism which often uses Michelangelo’s art in order to create pieces of intelligence; knowing how to work as the Michelangelo’s manner meant to participate to his genius and within this attitude there is no disruption with tradition but a continuance of it.

Another aspect which should be taken into consideration because it encourages the artistic innovation is the concept of empathy with the piece of art. With this term it is suggested the ability of identifying with another person and therefore even with his sensibility and his artistic production. This ability leads to an intimate negotiation of meanings between the producer and user and also implies the observer’s cultural background. This means that according to the quantity and quality of each one’s education – in other words, a sort of individual tradition – the reading of a piece of work and its possible quote in a new artistic product will be different from person to person.

3 – G. Klimt, Ritratto di Eugenia Primavesi

In order to give an example we can make reference to artists of different age which interpreted some of the traditional concepts in a totally individual manner. The first artist is the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862 – 1918). During his artistic career he reflected over the decoration’s role by creating amazing pieces of work, rich of tradition references.

Among the Artist’s favourite historical periods there is the Byzantine period which is characterized by the bright gold and precious materials, by the taste for the full covering of surfaces and the highlighted bidimensionality of images. He knew how to read back a secular tradition in light of the artistic tendencies of the end of 19th century by finding, in an essentially religious art, formal elements to reuse.

Klimt’s mission is to purify the prevailing nature of Oriental and Ravenna’s art (fig. 1) from the cultural background which produced it, by inserting themes and techniques in a new context; about the tradition refinement and allusion remain, while the sacredness gives way to a spiritualized matter with a laic and decadent vision.

The Byzantine stylistic features of the golden period remain transfigured also in the so-called blooming style in which the preciousness of the materials is replaced by a virtuous and deliciously chiseled painting (fig. 3); and it is here where the innovation seems accomplished because the tradition had been fully absorbed by the artist and it does not have any more a reason to be pointed out as much as it was understood. A Byzantine feeling still exists in this painting, which is ancient and modern together, perfectly inserted into tradition and yet undoubtedly innovative.